Did You Know? By stating, “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated,” the Articles of Confederation (formally ratified in 1781) asserted the dominant power of the states, while limiting the power of the national government. The ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1787, however, shifted the balance of power from the states to the national government. This alarmed Anti-Federalists, such as Virginia’s Patrick Henry, George Mason, Richard Henry Lee, and James Monroe, who feared the rise of a strong federal government at the expense of the states’ powers. To alleviate the concerns of the anti-federalists, the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which is part of the Bill of Rights) established that, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” While the language of the Tenth Amendment is very similar to that of the Articles of Confederation, interestingly the word “expressly” is absent, thus providing the national government with a high degree of latitude in defining and asserting its implied powers “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper,” as stated in Article I, section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. |

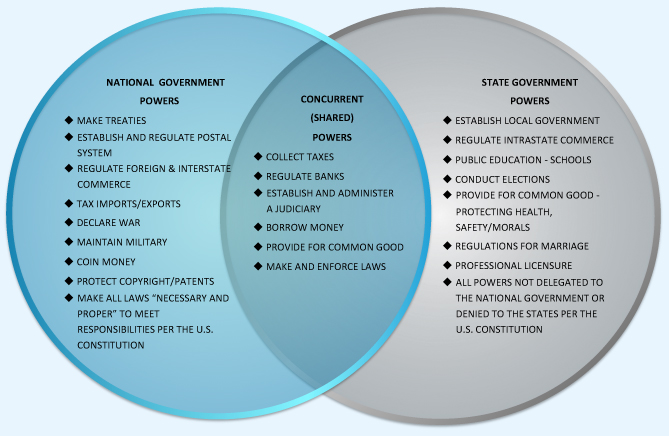

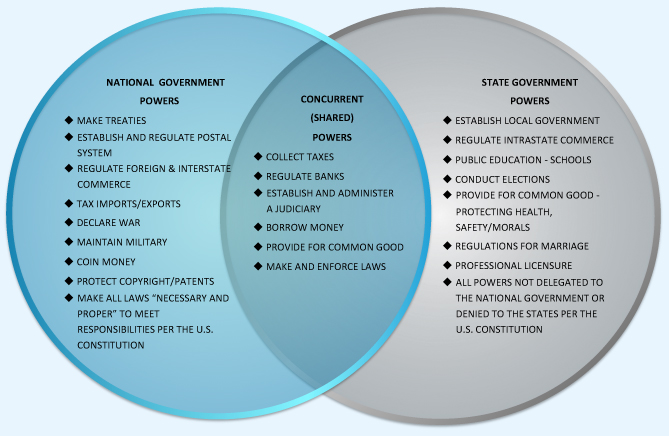

As the Venn diagram below shows, American citizens are served by both their federal government and their state government. Examples of areas where the national government has sole power include the ability to raise an army, declare war, coin money, establish a postal service, protect copyrights and patents, and make foreign treaties. Other policy areas such as education are left to the states. In our nation’s federal system, all powers not delegated to the national government or prohibited to the states are reserved to the states. This is guaranteed by the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Additionally, as the Venn diagram shows, states and the national government share certain powers (concurrent powers). These include, but are not limited to, the power to tax, the power to borrow money, to build roads, and to pass criminal justice laws. Conflicts between the state and national authority are often found in these concurrently held powers. Additionally, the spheres of powers held by each level of government are sometimes merged through the process of distributing federal money to the states. This process is known as the grants-in-aid system.

While the federal government may not be able to require state action in certain policy areas reserved for state regulation (such as education), the federal government is able to attach conditions to monies distributed to states. These requirements are known as mandates. If the states do not meet these strict conditions, they will lose the associated federal funding.

Examples of National Government Powers, State Government Powers, and Shared Powers

| Did You Know? There are two main types of federal aid to states. Categorical grants, which require federal aid to be used for specific purposes, are the main source of federal aid to states. Block grants, which are less specific than categorical grants, are sources of federal aid that are provided for general purposes. Block grants generally have fewer restrictions than do categorical grants. |

There are some powers that are denied to both the state and national governments. Neither of these governments can pass ex post facto laws or bills of attainder. Prohibition against ex post facto laws protects citizens from both the state and national governments creating laws that change the legal consequences of actions committed prior to the enactment of the new law. In short, you cannot be tried for something that you did before a law was created making that action illegal.

Prohibiting bills of attainder protects citizens from legislative action, at either the federal or state level, which inflicts punishment on individuals without judicial trial. Additionally, there are a number of powers specifically denied to both the national government and state governments. For example, the national government may not: use money from the U.S. Treasury without the approval of an appropriations bill, violate the Bill of Rights, or adjust state boundaries without the agreement of the state legislature.

In terms of examples of powers denied to the states, state governments may not: enter into treaties with countries or nations, declare war, coin money, impair obligations of contracts, or suspend a person’s rights without due process.